The 22nd 'official' James Bond film, QUANTUM OF SOLACE, is one of the most underrated of the series. This essay looks at the film's part in the Bond legacy, and in modern action cinema in general. It also looks at the film's influences, and its place in a series of like-minded films.

QUANTUM OF SOLACE took the crown of the most controversial Bond film from LICENCE TO KILL (1989), a film with which it shares a lot of similarities. Both are the sophomore outings for the actor portraying James Bond (Timothy Dalton in LICENCE TO KILL). They both divided fans for their focussing away from the tropes of the series in order to present a more grounded, violent, gritty thriller, departing from what many fans believe to be the essential elements of the films: humour, a touch of fantasy, sophistication, and escapism.

Both LICENCE and QUANTUM have Bond avenging the death of a woman he cared for (his friend Della Leiter/ his lover Vesper Lynd). In both films, Bond struggles to rein in his blinding thirst for vengeance and remain a dutiful MI6 agent. In the two films, Bond is considered a 'rogue' agent by his superiors, and hunted down by one of the intelligence services (MI6 in LICENCE; the CIA in QUANTUM). Bond is presented as a ruthless man in LICENCE and QUANTUM, and whilst this presentation of the character may strike some fans as un-Bondian, Bond was certainly presented as a man capable of being ruthless in the books, yet expressing distaste for killing in cold blood (something he did twice to earn his '00' status). Interestingly, Bond was actually presented as a man capable of killing in cold blood in the first 'official' Bond film, DR. NO (1962), where we see 007 (Sean Connery) execute Professor Dent (Anthony Dawson). As the series progressed and became more successful, the ruthless aspect of Bond's character was toned down, to the extent that when Scaramanga (Christopher Lee) describes Bond (Roger Moore) as an assassin in THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN GUN (1974), it feels a bit off the mark.

There are other, more superficial, similarities. Bond is helped by a beautiful female fellow operative (CIA informer Pam Bouvier/ex-Bolivian Secret Service agent Camille Montes) and also a male fellow operative ('Q'/Felix Leiter). An ally betrays his colleagues and sets off the plot (Ed Killifer/Craig Mitchell). The locations are earthy, humid and reminiscent of/ or are literally South American locations (Isthmus/Haiti, Bolivia). The climax occurs in or near a desert at the villain’s base of operations (Olimpatec Meditation Centre/Perla De Las Dunas). The end has Bond being invited to return to Secret Service duty - a little too neatly, I might add, in the case of LICENCE TO KILL.

At the very least the bravery of the two films in emphasising the rarely seen, ruthless side of Bond's character mark them as two of the most interesting and valuable additions to the canon.

(B) QUANTUM OF ROYALE

The Bond producers sometimes revisit the strongest themes or plot threads from the series. For example, THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH (1999) was influenced by FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE (1963) and ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE (1969). In fact, although chronologically the story of CASINO ROYALE is a kind of prequel to O.H. M.S.S. (Bond once again loses the woman he loves in the latter film), the 2006 version is an attempt to make a like-minded film - action-packed and exciting but also emotional, dramatic and luxuriously paced.

CASINO ROYALE had presented Ian Fleming's version of James Bond - a complex and extraordinary man who thrives on conflict but is still uncomfortable with killing in cold blood, and has a sense of righteousness and a romantic heart. The film added to this a Bond capable of making mistakes in judgment, and prone to arrogance and chauvinism. His defining traits were his stamina and his ability to never rest until the job is done, even when faced with certain death. When his heart is opened and broken by Vesper in the movie, it's a powerful conclusion. His chance to escape his soul-destroying vocation has been closed up again, his fate sealed. He is now again the 'blunt instrument' he perfectly embodies.

Director Marc Forster rings in the changes immediately in QUANTUM OF SOLACE. There is no gunbarrel introduction. Every official Bond film, except CASINO ROYALE, begins with one, the exception being ROYALE, where it follows the monochrome pre-credits sequence. The omission indicates immediately that Forster's film is a different Bond film, and that the ROYALE story is not yet done with. QUANTUM saves its gunbarrel to kick off the end credits crawl, sealing off ROYALE and QUANTUM as the 'introduction' to the 007 we all know and love.

The film begins with a gliding zoom across Lake Garda (complete with ominous, edgy David Arnold music), interspersed with quick-fire cuts of a car chase and of Bond with his 'cold mask' in full effect (the latter reminiscent of the introduction of George Lazenby in O. H. M. S. S. ). A sudden burst of machine gun fire from the heavies sets off one of the most excitingly filmed car chases in movie history. The rapid editing keeps one on the edge of one's seat, and serves to put the audience in the mindset of Bond as he negotiates the twists and turns of the roads whilst averting gunfire, oncoming traffic and police cars in pursuit. Bond is calm under (literal) fire, quick thinking, resourceful and ruthless. It's as exciting and thrillingly filmed as the car chase in Fleming's 'Moonraker' (1955) was thrillingly written. In the pay-off to the scene he displays sly humour ('It's time to get out'). The pre-credits scene sets the tone and pace of the picture.

Dan Bradley's fast-cutting, exhilarating, in-your-face action style was established in THE BOURNE SUPREMACY (2004) and THE BOURNE ULTIMATUM (2007), both directed by Paul Greengrass. Some complained that Eon had simply co-opted the BOURNE style for Bond. (Simon Crane handled the Haiti boat chase, actually filmed in Panama.) It has been said that the copious action scenes in the film - the car chase, the Siena footchase, the Haiti boat chase, the shootout in Bregenz, and the aerial dogfight in Bolivia (ending in a freefall skydive that was an original script idea for GOLDENEYE) - are impossible to follow and not suitable for the Bond franchise. Yet the scenes are very much part of the whole intent of the film - to thrust the viewer into the heart of the action and the heat of the moment.

Forster constructed each action scene to reflect an element: earth (the car chase, footchase, shoot-out in Bregenz), water (the boat chase), air (the aerial dogfight) and fire (the climax). He was hands-on in the action sequences, telling ABC.Net: '... I wanted to make it a very tight and fast movie. Sort of this rush, almost like a bullet, that it keeps us at the edge of the seat from beginning to the end. And I felt I wanted to, on purpose, as it is a sequel to CASINO ROYALE, still make it stylistically very different and my own ... I sort of designed the film like that.' This extended to nixing the idea of using flashbacks to refer back to ROYALE. Some viewers who had not seen ROYALE complained that the film was difficult to follow (despite the film being heavily promoted as a direct sequel).

It was Forster's decision to bring Bradley onboard, using his aesthetic to separate ROYALE and QUANTUM, and bring a more immediate pace to a film that was in the end, partly a drama about resolution. The result was the fastest-paced and shortest movie in the series at 106 minutes, coming off of ROYALE, the longest film in the series, at 144 minutes.

Bradley, in collaboration with editors Rick Pearson and Christopher Rouse, changed the landscape of modern action cinema with THE BOURNE SUPREMACY (2004), something Peter Hunt also achieved way back in 1962 with DR. NO. Their style is in keeping with Hunt's editing style on the first Bond movies, and in particular his fight scenes in his directorial outing, O. H. M. S. S. Matt Damon's brutal fight with Marton Csokas in THE BOURNE SUPREMACY owes a lot to the brilliant Sean Connery/ Robert Shaw train carriage fight in FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE. Forster hired SUPREMACY's co-editor, Rick Pearson, to work alongside his regular editor, Matt Chesse, on QUANTUM, clearly desiring similarly visceral, thrilling results.

Another precedent to Bradley's style can be seen in Alexander Witt's action work on the Ridley Scott films GLADIATOR (2000) and BLACK HAWK DOWN (2001). Witt sometimes reduces frames to emphasise movement; Bradley uses rapid editing to achieve the same aim, letting the audience fill in the missing information, in a similar way to how Hunt would over-crank or eliminate blows in fight scenes or entrances into rooms. Both Witt and Bradley (and Hunt) have a visceral feel to their work.

Witt worked on THE BOURNE IDENTITY (2002) and was replaced by Bradley for the sequel. The same thing happened on CASINO ROYALE. Bradley was a natural successor to Witt for both movies, being in the same vein but with a definite style to his own. He was 'the same, but different' - the audience requirements for every Bond picture, as identified by Bond screenwriter Christopher Wood (1977's THE SPY WHO LOVED ME, 1979's MOONRAKER).

(D) QUANTUM OF HEART

QUANTUM echoes O. H.M.S.S. in that Bond spends the whole of the film on a mission that thematically is secondary to the concerns residing in his heart. The film's narrative reflects the confused mindset of Bond himself. As Bond learns more about the machinations of Quantum and the truth behind Vesper's betrayal, he learns more about himself, whether he is the 'blunt instrument' 'M' describes him as in ROYALE, capable of putting Vesper behind him, or a man wounded by betrayal, out for vengeance and not capable of doing his duty as an agent. The arc of Bond's character in QUANTUM cuts deeper than the one he had in ROYALE.

QUANTUM echoes O. H.M.S.S. in that Bond spends the whole of the film on a mission that thematically is secondary to the concerns residing in his heart. The film's narrative reflects the confused mindset of Bond himself. As Bond learns more about the machinations of Quantum and the truth behind Vesper's betrayal, he learns more about himself, whether he is the 'blunt instrument' 'M' describes him as in ROYALE, capable of putting Vesper behind him, or a man wounded by betrayal, out for vengeance and not capable of doing his duty as an agent. The arc of Bond's character in QUANTUM cuts deeper than the one he had in ROYALE. The film continues the idea of the action scenes reflecting and developing character that was begun in ROYALE, eg. Bond's journey from cold rage to catharsis is evident in the way he is able to finally control his violence. He didn't need to kill Edmund Slate (Neil Jackson) in Haiti, but he leaves Greene stranded in the desert at the end of the film (after he has given up his Quantum secrets), knowing he will be found and killed by his own people. Bond spares Yusef (Simon Kassianides), the man who drove Vesper to betrayal, so that he can be 'sweated' by MI6. Bond's protective nature towards women is revealed when he helps Camille (Olga Kurylenko) to emotionally prepare to murder General Medrano (Joaquin Cosio) in the desert ('You only need one shot. Make it count.'). It is further revealed by his willingness to put her out of her misery when she believes she is going to burn to death, like her family. Meeting Camille makes Bond realise what he could easily become - a person consumed by hate and vengeance, and it begins his healing and maturing process. The pair learn from each other, and their twin mindset brings them too close for comfort. Which is why (apart from the breakneck pace of the film) they don't actually get to consummate their mutual attraction - a twist on the expectaions of a Bond film.

In ROYALE, Bond learned the hard way that you cannot trust anybody. In QUANTUM, he learns far more about himself: that he is capable of love (Vesper) and empathy (see his treatment of Camille above), but that he is also capable of the clear-headedness that goes hand-in-hand with the ruthlessness of his vocation. Michael G. Wilson explained that '...he's tempted by revenge and tempted by becoming a cynic, by losing his humanity. He has to fight all of these things.' The close of QUANTUM has Bond where he is at the end of the 'Casino Royale' (1953) book, ready to do his duty in the manner and mindset required. QUANTUM OF SOLACE is in effect, the epilogue to CASINO ROYALE. Instead of making a bigger film, Eon chose to in fact make a smaller, more intimate, in many ways even less fantastical film.

The film doesn't even try to maintain complete continuity between itself and its predecessor, an aspect many believe to be a major flaw. Wilson announcing that QUANTUM would begin directly after ROYALE's climax inadvertently created a baton for some to hit the film with. Bond is wearing a different suit and haircut than the last scene of ROYALE, and 'M' now has a new, more modern office. It's clear that, as with the two BOURNE sequels, the beginning of the second film (QUANTUM/ ULTIMATUM) makes one immediately question what we thought was the timeline of the ending of the first film (ROYALE/ SUPREMACY). (Vesper's Algerian loveknot is also a different version!)

The only links to ROYALE in QUANTUM are Bond's trauma over Vesper's death and betrayal, and the investigative lead in Haiti being tagged funds from Le Chiffre (Mads Mikkelsen) and Mr White (Jesper Christensen), from the previous film. Otherwise it is a new Bond adventure. Which means that with QUANTUM, we get the best of both worlds - a brand new Bond movie (and a unique one at that), and one that continues Bond's arc from the previous film, bringing more depth, nuance and resonance than usual.

Stylistically, it contrasts and complements ROYALE. QUANTUM is lean, direct and concise, where ROYALE was lengthy, melodramatic and luxuriously paced. The opening car chase could be the missing car chase potentially set up in ROYALE when Bond pursues Vesper's 'kidnappers'. The films share a post-credits footchase, and villains (Le Chiffre/ Dominic Greene) who are like Largos (THUNDERBALL, 1965), rather than Blofelds, and are both executed by Quantum, the organisation they work for. Both Vesper and Camille are enigmatic, headstrong, beautiful women with pain in their hearts. Both films end with a revelation that prompts Bond to question what he thought he knew about Vesper - her betrayal (ROYALE) and the fact she was manipulated into betraying him in the first place and did all she could to spare Bond's life, including dying for him (QUANTUM). The two films also end with Bond being invited back in the fold by 'M'.

(E) QUANTUM OF INFLUENCE

Quantum having their meeting through earpieces whilst watching 'Tosca' in Bregenz feels modern, a clever a twist on the elaborate Ken Adam-designed SPECTRE meeting room from THUNDERBALL (1965). It's also reminiscent of the ending of Hitchcock's THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934/ 1956), set during a Royal Albert Hall music performance. Mathieu Almaric's Dominic Greene has some of the pitiful villainy of Peter Lorre, who appeared in the 1934 version. Another nod to Hitchcock is the naming of a minor villain, Guy Haines (Paul Ritter). It is also the name of Farley Granger's lead character in STRANGERS ON A TRAIN (1951).

Villainy, obfuscated by bureaucracy and hidden in plain view, was also an element of Robert Towne's screenplay for Roman Polanski’s CHINATOWN (1974), which was also concerned with the power of those controlling water as a resource. Fittingly, Mathieu Almaric bears more than a passing resemblance to Polanski, who also appeared in CHINATOWN as the hood who slits Jack Nicholson's nostril.

At one point Bond tells 'M', regarding Miss Fields's murder, that 'It's just misdirection', referring to Quantum's talent for misdirecting their opponents. The film itself enjoys misdirecting the audience. It resolutely IS a Bond film, but it subverts expectations. Bond wears a tuxedo, but it's one he steals from the enemy. There are funny quips, but the funniest one is delivered in Spanish by Bond. There's an evil plan for world domination, but Bond is in on it during its early stages instead of when the enemy is ready to pounce. It's also a plan that has an endgame rather than involving an all-out strike. There's a Bond girl with a name to rival Pussy Galore (GOLDFINGER) or Holly Goodhead (MOONRAKER), but you never get to hear it in the film. Gemma Arterton's character is named Strawberry Fields only in the end credits. Greene has a henchman, Elvis (Anatole Taubman), but, like Greene himself, he is physically unremarkable (he even wears a hairpiece), and unlike Greene, is quite a sad and comic character.

Chile’s Atacama Desert was chosen as the location for the climax because Forster believed it represented Bond's 'isolation and loneliness'. It is also a location reminiscent of the eponymous Death Valley location in Michelangelo Antonioni's ZABRISKIE POINT (1970). That film also has an incongruous desert estate like QUANTUM’s Perla De Las Dunas (in real life, part of the Paranal Observatory).

Marc Forster told Indie Wire that ''I was very aware going into it that my objective ... was to make it more like a '70s, very straightforward revenge movie, and that sort of pace was my point of view.” The '70s were a high tide for political, conspiracy and revenge thrillers, inspired by the shifting culture, the cynicism that grew at the tail end of the 'Swinging '60s' (and that brief Summer of Love), and the growing concerns over Vietnam, political terrorism, the oil crisis and Watergate. A taste of the time can be achieved by viewing such edgy, challenging, paranoid thrillers as THREE DAYS OF THE CONDOR (1975) and THE PARALLAX VIEW (1974) (both co-written by NEVER SAY NEVER AGAIN's Lorenzo Semple Jr), political thrillers like ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN (1976) and pacy, ultra-violent revenge thrillers like DEATH WISH (1974). QUANTUM has echoes of these kinds of films and is one of the qualities that makes the film a rich and unique entry in the series. However, it is this tone that has divided Bond fans and caused controversy amongst them. Ironically, during the '70’s, Eon and United Artists' response to the times was to make films that would allow audiences to forget their troubles. Sean Connery's final Bond film for Eon, 1971's DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER, ushered in the series’ direction of light-hearted adventure movies which was much derided at the time by the same fans who now dislike the more serious direction taken by QUANTUM.

(F) QUANTUM OF META

Whilst no elements of the original short story are utilised in the film, there are certainly Flemingesque elements. Camille Montes is a classic Fleming 'wounded bird'. Although a drop-dead beauty, Camille is humanised by a Flemingesque physical defect: a scarred back courtesy of Medrano leaving 'his mark' on her when she was a child. She shares facets with the character of Judy Havelock from the 1960 short story 'For Your Eyes Only' (housed in the eponymous collection that also included 'Quantum of Solace'), both being women avenging the death of murdered parents who inadvertently come into contact with Bond and end up working with, and being helped by him. The character was renamed Melina Havelock and portrayed by Carole Bouquet in the 1981 Bond film FOR YOUR EYES ONLY. In both QUANTUM, and the F.Y.E.O. short story and film, the nature of revenge is a theme.

Whilst no elements of the original short story are utilised in the film, there are certainly Flemingesque elements. Camille Montes is a classic Fleming 'wounded bird'. Although a drop-dead beauty, Camille is humanised by a Flemingesque physical defect: a scarred back courtesy of Medrano leaving 'his mark' on her when she was a child. She shares facets with the character of Judy Havelock from the 1960 short story 'For Your Eyes Only' (housed in the eponymous collection that also included 'Quantum of Solace'), both being women avenging the death of murdered parents who inadvertently come into contact with Bond and end up working with, and being helped by him. The character was renamed Melina Havelock and portrayed by Carole Bouquet in the 1981 Bond film FOR YOUR EYES ONLY. In both QUANTUM, and the F.Y.E.O. short story and film, the nature of revenge is a theme.Mathis's 'Heroes and Villains' speech from 'Casino Royale' (1953) is transported to a scene at his villa in Talamone, Italy. Mathis’s fate has a precedent in that Raymond Benson had him blinded by the villain in his penultimate continuation novel 'Never Dream of Dying' (2001). Forster's shot of the iguana in the Atacama desert feels very Fleming: the 'Diamonds are Forever' (1956) novel opens and closes with descriptions of a scorpion in the African desert. Unused settings and scenes also came from Fleming. The deleted cliffhanger ending of Bond seemingly dying at the end at the hands of Mr White came directly from the finale of 'From Russia, with Love' (1957). Bond avenging the death of a woman he loved was a facet of 'You Only Live Twice' (1964), the sequel to 'O. H.M.S.S.'. Paul Haggis had originally set his climax in the Alps, as Fleming (and the filmmakers) had in 'On Her Majesty's Secret Service' (1963). The shot of Vesper's Algerian loveknot in the snow was likely influenced by the 1965 UK cover of the latter novel, which has a gold ring in the snow, with spilled blood beside it.

QUANTUM also tips its hat to the movie series. The iconic image of Jill Masterson (Shirley Eaton), dead on her front, painted in gold from head to toe in GOLDFINGER is homaged by the similar death of Miss Fields, this time covered in oil. It's a clever piece of publicity misdirection as it led audiences to believe, like the CIA in the film, that Quantum was concerned with oil, making the reveal more of a surprise.

THE SPY WHO LOVED ME (1977) is referenced explicitly: Bond (Roger Moore)’s cover name is Robert Sterling, and his method of dispatching of Guy Haines's bodyguard (Derek Lea) is similar to the fate of Stromberg's henchman, Sandor (Milton Reid). Bond and Anya (Barbara Bach)’s desert trek, dressed in a black tuxedo and a black cocktail dress respectively, is also evoked by Bond and Camille walking in the desert in similar apparel.

(G) QUANTUM OF HUMANITY

Courtesy of Forster's frequent cinematographer Roberto Schaefer, QUANTUM has a a travelogue feel and level of lushness and gloss that has probably been missing from the series since Jean Tournier's work on MOONRAKER (1979) more than 25 years previously. That said, it shares a desire with Michael Mann's MIAMI VICE (2006) to have real, dangerous, unpredictable (Central/ Southern American) locations, with locals as extras to add authenticity. VICE also starts in media res and has shadowy villains, a difficult central romantic relationship, and heroes who have to trust their instincts in order to survive. (Like QUANTUM, it also faced criticism for failing to live up to audience expectations - the film being dissimilar to the original '80s TV series.)

The world of QUANTUM is opulent, but lived-in and deadly (reflected by Dennis Gassner's more pared-down design work), and even the beautiful buildings, events and locations have other things going on underneath. The 'Greene Planet' cover is a perfect example of this theme - Greene is promoting one thing (environmental protection), whilst actually doing the opposite (exploiting the land and its inhabitants in order to control the water supply).

Quantum's plan is to engineer a military coup in Bolivia which will restore exiled leader General Medrano to power. The organisation has misled Medrano into believing they are helping him in exchange for the rights to any oil they find in Bolivia, when what they are really after is the country's water supply. They have created dams to steal the country's fresh water supply, and Medrano is forced to sign over Bolivia's utility rights to Quantum in order to return to power. Their real crime is a moral one: the people of Bolivia are suffering because of lack of water, and on top of that Quantum are restoring to power a leader who, if his affinity for rape and murder are any indication, is an evil dictator. The story has roots in reality: the Bolivian Cochabamba protests in the year 2000 saw demonstrators protest against the privatization of the country's water works after the multinational corporations involved caused the price to use this basic resource shoot sky high.

In keeping with 'M's insistence that Bond look at 'the bigger picture', so does Bond and so should we. In Quantum's overall plan for world domination, the 'Tierra' project is only one small branch of the tree, but it's an important one. Quantum, unlike SPECTRE, is not concerned with a huge strike against the world for financial benefit. Like a business planning a corporate takeover, it is more concerned in building it's power step by step so that when it's goal is achieved, its power is total. If QUANTUM represents the modern Bond film, then Quantum represents the modern SPECTRE. (Given Paul Haggis's leaving of the Church of Scientology in 2009, some have wondered if he based Quantum on the organisation.)

Forster also shows how the machinations of the villains and the violence of Bond's world affect the innocent. A tourist gets accidentally shot by Mitchell in Siena. A hotel receptionist (Oona Chaplin, the grand-daughter of Charlie Chaplin) suffers a near-rape at the hands of Medrano. The citizens of Bolivia will thirst for water because Quantum is creating a drought. We get to learn that Mitchell has a family, making even his death a tragedy.

The film also allows time to show the 'come-down' from violence, and the effect violence has upon the immediate environment. Bond returns to the safe house in Siena after giving chase to Craig Mitchell (and killing him), and the immediate environment outside the safe house, previously the site of a Palio horse race with a huge crowd, is now empty, with police sirens in the distance. The actual safe house is empty too, with blood flowing down a gutter. We also see Bond's come down after his rescuing of Camille in Haiti, and his glow is a very Bondian moment - the smile of a man who has just identified and engaged the enemy, made a blow against him and prevented him from achieving his ends.

(H) QUANTUM OF LE CARRE

Paul Haggis admitted whilst working on the script that the film was an 'odd mix of Le Carre and Fleming'. Haggis was no doubt referring to the political intrigue of the story, with both the CIA and MI6 willing to deal with Greene if it means getting their hands on the oil supply they have been duped to believe he has found in Bolivia. The CIA are even willing to get rid of Bond to ensure the deal goes through.

Paul Haggis admitted whilst working on the script that the film was an 'odd mix of Le Carre and Fleming'. Haggis was no doubt referring to the political intrigue of the story, with both the CIA and MI6 willing to deal with Greene if it means getting their hands on the oil supply they have been duped to believe he has found in Bolivia. The CIA are even willing to get rid of Bond to ensure the deal goes through. The author is concerned with the emotional costs of espionage, and the sordid reality of counterintelligence, and in 1965, one couldn't get two espionage films as different as each other as THUNDERBALL and THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD. It's arguable that Le Carre's work exists in opposition to Fleming's work, and in an odd way, the pair contrast and complement each other. Fleming doesn't shy from showing what espionage and the act of murder do to Bond's psyche, but in the opening chapter of 'Goldfinger' Bond describes regret as 'unprofessional' (as 'M' does at the close of QUANTUM to Bond) and leading to 'death-watch beetle in the soul'. Le Carre's work has that very air of regret embedded in it's spine, and the cynicism that Michael G. Wilson sees Bond as attempting to avoid in QUANTUM.

Le Carre, despite writing in the espionage genre, is no fan of 007. He told Malcolm Muggeridge in a 1966 interview for BBC Radio: 'I dislike Bond. I'm not sure that Bond is a spy. I think that it's a great mistake, if one's talking about espionage literature, to include Bond in this category at all.' He went on to describe Bond as 'an international gangster'.

Despite Le Carre's distaste for 007, Bond screenwriters like Paul Dehn (GOLDFINGER), John Hopkins (THUNDERBALL), and Jeffrey Caine (GOLDENEYE, 1995), all found themselves working on adapatations of Le Carre's books, Neal Purvis and Robert Wade (THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH to SKYFALL) and Peter Morgan (early drafts of SKYFALL), seeing their efforts unfilmed and rewritten respectively. Sean Connery gave one of his finest performances in THE RUSSIA HOUSE (1990), and Pierce Brosnan was equally excellent in THE TAILOR OF PANAMA (2001), playing a role that in the original 1996 novel could, ironically, be seen as Le Carre's version of what a real-life 007 might be like (he describes his appearance and background in much the same way as Fleming did).

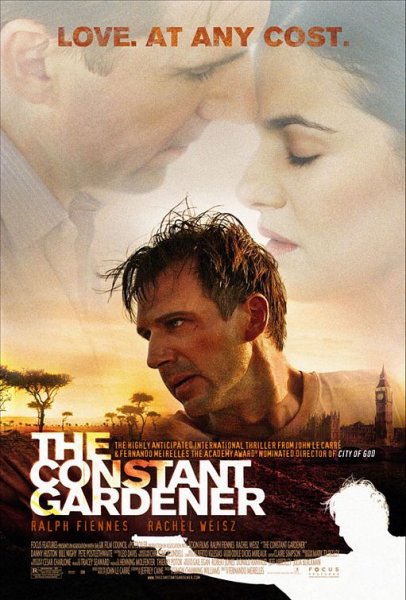

THE CONSTANT GARDENER (2005) was based on the 2001 novel by Le Carre (and adapted by Jeffrey Caine). It is one of his more overtly political espionage thrillers, and is an angry condemnation of the exploitation of the Third World by big-business pharmaceutical companies. Like Bond in QUANTUM, Ralph Fiennes (SKYFALL) tries to uncover the truth behind the death of the woman he loved (Rachel Weisz, in real-life, Daniel Craig's wife), and the espionage elements of the plot are secondary to the emotional journey he is undergoing in his heart. By the end of the story, he has learned he wasn't betrayed by his lover (wife). Both films involve questionable ethics on the part of the security services. And the two films share beautiful but earthy locations (Kenya/ South America) that reflect the soul of the lead character. Both films end in the desert and make use of local extras to add to authenticity and emphasise the human cost of the issues involved in the actions of the 'villains'. THE CONSTANT GARDENER also, like QUANTUM, had an unorthodox choice behind the camera: Brazilian filmmaker Fernando Mereilles, who had directed the acclaimed crime docu-drama CITY OF GOD (2002).

(I) QUANTUM OF BOURNE

The direction taken by QUANTUM did not come out of thin air. Concern over big-business exploitation of the less fortunate parts of the world, the CIA's intrusive role in Middle East politics to ensure access to an oil supply, and in a post 9/11 world, the autonomy of the CIA or factions of it were also evident in other films contemporary to QUANTUM OF SOLACE.

Released the same year as THE CONSTANT GARDENER was the geo-political thriller SYRIANA, written and directed by Stephen Gaghan (Oscar winner for writing TRAFFIC, 2000) and featuring Jeffrey Wright, Felix Leiter in ROYALE and QUANTUM. Like TRAFFIC, SYRIANA has several interconnected stories located in different cities and countries (US, Switzerland, Spain, Lebanon, Iran), and is concerned with the human cost of business - here maintaining the US's oil supply, in TRAFFIC the narcotics trade. QUANTUM shares the location-hopping, the beautiful but lived-in, shot-on-location look of the photography, and the cynical politics: in both films the CIA is willing to commit murder, even if it is one of their own agents, or in the case of QUANTUM, a 'brother' agent, to ensure the US's oil supply from the Middle East. Both films also suffered under the weight of expectation (many it seemed expected another TRAFFIC, which had been directed by Steven Soderbergh and not Gaghan), and were accused of confusing storytelling, when all was asked was close attention and an open mind.

These ethical issues were arguably in the cultural ether. In 2008, THE DARK KNIGHT replaced THE BOURNE SUPREMACY as the game-changer for the genre, with its blending of real-world fears where people are not out to destroy the world but to destabilise it from within for their own ends, and where the emotional impact of the characters’ choices have a real resonsance in the story. This new performance-driven action movie necessitated deeper, richer performances from the actors. Released later the same year, QUANTUM more than met the gauntlet thrown down by THE DARK KNIGHT.

The success of THE BOURNE IDENTITY in 2002 has regularly been viewed as an influence on the less fantastical, gritty approach afforded to CASINO ROYALE in 2006. Such an approach was already in the works as far back as 2003 when Eon and MGM were developing the $60m movie JINX, featuring Halle Berry's character from DIE ANOTHER DAY (2002). It's interesting that Eon was more interested in making a spin-off film rather than a new Bond film directly after DIE ANOTHER DAY. But then Michael G. Wilson did reveal to The New York Times in 2005 that 'I was desperately afraid, and Barbara was desperately afraid, we would go downhill... We (were) running out of energy, mental energy. We need(ed) to generate something new, for ourselves.'

Neal Purvis and Robert Wade had written a first draft that had impressed everybody, including director Stephen Frears (director of, amongst other diverse films, the hard-hitting thrillers/ dramas THE HIT, 1984; THE GRIFTERS, 1990; and LIAM, 2000), but MGM pulled the plug, possibly because of the disappointing business generated by Halle Berry's CATWOMAN (2004), and female-led action pics in general such as CHARLIE'S ANGELS: FULL THROTTLE (2003) and KILL BILL, VOL. 1 (2003). The writers confirmed to hmss.com that it was 'a fairly down-to-earth espionage picture', and that when they began talking with the producers about the next film, it was soon made clear it would be CASINO ROYALE and it 'was obviously going to be in the same vein'.

If THE BOURNE IDENTITY had a discernible influence upon CASINO ROYALE, it's likely that its success showed Eon that a Bond movie, in the more low-key, character-based, 'down-to-earth' style of the JINX movie and fittingly, the 'Casino Royale' book, would be accepted by the masses. That the film had made around as much profit as DIE ANOTHER DAY on more than half the Bond film's budget cannot have escaped Eon and Sony's notice either. That said, the film's influence on the new direction of the Bond series has been overstated by many. SUPREMACY certainly influenced the style of QUANTUM to be sure in that Bradley was hired to create similarly constructed action sequences. But if the influence goes any further, then one could equally ask if Jason Bourne was influenced by Bond's initials, his amnesiac state at the end of the 'You Only Live Twice' book, and his emotional state at the end of ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE (both characters lost their wives).

Bond and Bourne are as influenced by each other as anyone working in a similar field would be. It's also worth remembering that QUANTUM is absolutely not offering a similar experience to a BOURNE movie. The world of the Bourne movies is limited in scope. The locations could be anywhere and are pretty anonymous. The movies are all about Bourne's story and not 'the bigger picture' of international politics. The action is minimalistic. The world of Bond/ QUANTUM is international and the locations are integral to the story, tone and feel of the movies (Forster commented that the script was rewritten to suit the locations). This particular film (and ROYALE) are much more concerned with Bond's personal journey, but the stakes are not just emotional but global. The action might be more minimalistic in this film, but I am yet to see a Bourne film that involves elegant Bondian tropes like Aston Martins, tuxedos, beautiful women in cocktail dresses, aerial dogfights,Tosca, and the villains' headquarters in the desert. The importance is in the details. Bond is Bond. Bourne is Bourne. They swim in the same waters, but they are different beasts.

(J) THE BIGGER PICTURE

Whilst many are concerned with who influenced whom, it very much seems that whilst the Bond series created the modern action movie as we know it, it is now part of the new genre it created, and helps to develop it by responding to the audiences' and their own needs for change. Sometimes it leads the pack (CASINO ROYALE), and sometimes it is more part of the pack (QUANTUM OF SOLACE). 80s action blockbusters like COMMANDO (1985) and DIE HARD (1988) owe a debt to 007 with their witty double-entendres deflating the effect of the explosive violence. LICENCE TO KILL was an unsuccessful attempt to capture some of that audience share. 'Rebooting' was in the air in the 00s, with studios trying to bring budgets down, franchises losing their steam, and lead actors getting older and not wanting to repeat themselves, especially if it meant not receiving significantly larger paycheques. Audiences wanted to see their favourite characters, but in a different light. And the events of 9/11 ushered in a feeling of guilt and revulsion at action cinema that was frivolous and didn't in some way reflect the concerns of the audience. Action heroes heroes were no longer invincible, were conflicted and asked difficult questions of themselves.

THE BOURNE IDENTITY opened nine months after 9/11 and despite deep concern from its makers that it would be rejected by audiences, was the perfect movie for the times. Interestingly, the most influential reboot, Christopher Nolan's BATMAN BEGINS (2005), seems to have been influenced by GOLDENEYE a decade earlier (his 2010 film INCEPTION used O.H.M.S.S. as the model for the snowbound action scenes, and he is an unabashed fan of the series). Both films spend a while setting up the new version and new world of the lead character, which is less glamorous and more gritty but still has a 'heroic' sheen; Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman) and his gadgets are clearly inspired by 'Q' (Desmond Llewelyn) and his handiwork; Christian Bale is quite Bondian in his scenes where he tries to convince people he's a billionaire playboy. For all its attempt to reinvent, BATMAN BEGINS is smart enough to keep all the motifs that audiences love, in much the same way a Bond film is always unmistakeably a Bond film. Both films acknowledge the ridiculousness of its hero in a realistic, modern setting, but by the end of the film, what we have is a restatement of the virtues of Bond/ Batman rather than a radical reinvention. The Bond series has re-booted itself after each film, and especially so with the introduction of a new actor playing Bond. The series has lasted fifty years by adapting where it needs to, and preserving its essential elements. The success of the series, with 22 (official) versions of essentially the same story and six different actors, has proven to filmmakers and studios that the reboot concept works. As such, how much the rebooting of Bond was influenced by Bourne, Jack Ryan (2002's THE SUM OF ALL FEARS was a franchise reboot, and Ryan is similarly uncomfortable with killing and operates in a shadowy political world) et al is negligible for a series that has rebooted itself time and again and pioneered the practice, just not as overtly as they did with CASINO ROYALE.

Any action hero, especially in the espionage genre, owes a nod to 007 in either his literary or cinematic form or both. Someone once said that The Beatles influenced every band after - bands either wanted to homage them or make as different music as possible. The same could be said for Bond.

QUANTUM OF SOLACE is a unique Bond movie in that it is very much a Bond movie, but is also a bold and ambitious attempt to have a Bond film reflect the world we live in and reverberate in the character of Bond himself. Part of a series of similarly concerned films, it is one of the richest and most exciting Bond films, as well as one of the most artistically and emotionally satisfying. It will be interesting to see how much SKYFALL will be influenced by the film.

RECOMMENDED VIEWING: All the films mentioned in this piece are worth watching to gain a deeper understanding, enjoyment and context for QUANTUM OF SOLACE.

My article on the making of the film can be read here.

SOURCES:

'Bond Franchise is Shaken and Stirred' by Sharon Waxman, New York Times, 15th October 2005.

'Bond Week Interview: QUANTUM OF SOLACE Director Marc Forster' by Alex Billington, Firstshowing.net site, 11th November 2008.

'Casino Royale' by Ian Fleming, Jonathan Cape, 1953.

'The Constant Gardener' by John Le Carre, Hodder & Stoughton, 2001.

'David Stratton Interviews Daniel Craig and Marc Forster', ABC Net At The Movies, November 2008.

'For Your Eyes Only' (collection of short stories) by Ian Fleming, Jonathan Cape, 1960.

'Goldfinger' by Ian Fleming, Jonathan Cape, 1959.

'HMSS Interviews Neal Purvis and Robert Wade', HMSS.com, 2007, currently offline.

'James Bond Series Takes a QUANTUM Leap' by Anthony Breznican, USA Today, 4th April 2008.

'James Bond Was a Neo-Fascist Gangster, Says John Le Carre' by Anita Singh, Telegraph UK site, 17th August 2010.

'Marc Forster Interview, QUANTUM OF SOLACE', Moviesonline site, November 2008.

'Marc Forster Talks WORLD WAR Z, QUANTUM OF SOLACE and The Risk of Failure' by Todd Gilchrist, The Playlist site, 11th September 2011.

'On Her Majesty's Secret Service' by Ian Fleming, Jonathan Cape, 1963.

'Quantum of Solace'- Review by Craig Arthur, 'A Decade In Review: The Best Spy Films, Part II - 2004-2009'.

'Quantum of Solace'. Wikipedia entry.

Paul Rowlands is a Japan-based writer. After completing a BA Humanities course (majoring in English and Science) at the University of Chester, he moved to Japan in 1999. He writes for the James Bond magazine, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, and has had an almost lifelong obsession with cinema, something the advent of DVD only increased.