Why did you want to make the transition from rock music to film?

I had done The Concert for Bangladesh in 1971 for George Harrison, and most of the people I wanted to work with didn't want to go on the road anymore. Dylan and The Band had quit, The Beatles had finished, and I didn't really want to work with David Bowie or Alice Cooper who were big deals at that time. So I decided to come to Hollywood and see who I could meet to try and get into the film business. Jay Cocks, who was then a writer at Time Magazine (he had done a cover story on The Band), gave me the name of a young film editor called Martin Scorsese.

What kind of films were you interested in making?

I was a fan of European neo-realist cinema, and liked De Sica, Visconti, Antonioni and early Fellini. I also liked the French New Wave - Truffaut and Godard. I liked 'street film'.

Had you seen any of Scorsese's work prior to meeting him?

No, I hadn't. But after we met he arranged screenings of all his student films and the two feature films he had made (WHO'S THAT KNOCKING AT MY DOOR, 1967 and BOXCAR BERTHA, 1972).

What was your first impression of Scorsese?

He was nervous and very high-strung. He wore a really long, black leather jacket that looked like something an SS officer would wear. It was literally down to his ankles. This was the middle of the summer! He was really intense and had a lot of energy. I had been around a lot of laid-back rock 'n' rollers all my life so it was different and fun.

What was your initial reaction to the script?

It was great, I liked it a lot. It was very personal and very different - it had a guy talking to God, for example! It had a lot of interesting elements. I didn't identify with it. It wasn't my life, but you didn't need to be an Italian-American or familiar with Italian cinema to be able to understand it. I did at least understood the Catholic guilt elements of it.

How different was the script to the finished film?

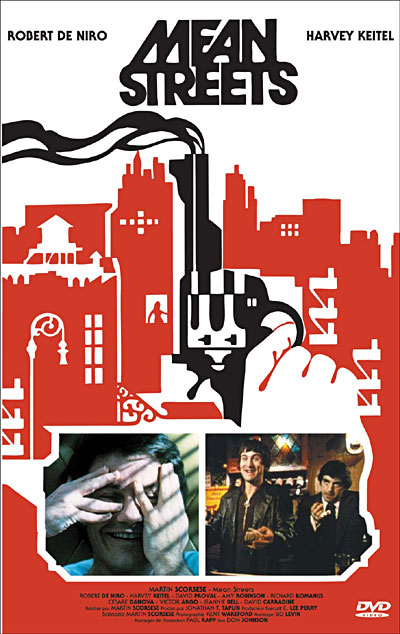

It was very close. Literally we only changed the name of the script (from 'Season of the Witch', the name of the bar Charlie dreams of owning in the film). Jay Cocks was the one who suggested the title MEAN STREETS. He got it from a Raymond Chandler quote ('The Simple Art of Murder', 1950: "But down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid."). There were very little changes. After I had agreed to produce the picture, Marty showed me these three little books in which he had storyboarded the entire film, shot by shot. He was so prepared.

When you came on board was the film still being conceived as a sequel to WHO'S THAT KNOCKING AT MY DOOR?

You could see that it was the same Harvey Keitel character, but only about 300 people had ever seen that movie so it didn't really mean anything.

How did you raise the money for the budget?

The movie was budgeted at $4000, 000 but we got out of control with the music and other post-production expenses, and the picture ended up costing about $500, 000. It was about half my savings and the other half came from a friend of mine in Cleveland. Marty had arranged for Roger Corman to distribute the picture as a way to encourage me to come on board. But we never did anything about it. He never put a cent into the film, so the offer of distributing it...I was like "Thanks a lot! That's not going to help!" (Laughs.)

When did Warners get involved?

After we finished. We trundled the prints around, and John Calley at Warners bought it. But as soon as Warners bought it I got the feeling that they were not that enthusiastic about it. It was just a low-budget movie for them. So I asked if I could buy back the European rights, and they agreed. We went to Cannes with the film and sold the rights.

Do you have any strong memories of Cannes?

I had actually been to Cannes in 1969 with Robbie Robertson, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko and Albert Grossman (Dylan's manager). Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda and all those guys had brought EASY RIDER. The whole thing was the craziest situation I have ever seen in my life. We were at a party and Rick Danko snorted something that wasn't what he thought it was and it put him to sleep. We had to take him to a hospital. It was a nightmare.

The strongest memory of the time I went there in '73 with Marty was meeting Federico Fellini. Jay Cocks was interviewing Fellini and invited Marty and I over. Jay told Fellini how brilliant MEAN STREETS was, and the guy who ran Federico's distribution company, Titanus, came in the room. Fellini told him "This is Martin Scorsese, a new Italian-American filmmaker. He has just made the most brilliant film I've seen in five years. " He totally bullshitted him! He hadn't even seen the film yet! The distributor wanted to buy the film on the spot so we went and made a deal with him about an hour later! It was amazing. By the way, when Fellini saw the film later on, he loved it.

Did you meet with a lot of actors for the film?

Marty had Harvey Keitel set in stone in his mind. Brian De Palma suggested Bobby De Niro would be really good. They had done three films together. We read with him once, and it was a simple decision to cast him. He was like a live-wire, amazing. Once we had those two then we got the rest of the cast from people we knew from Jon Voight's acting workshop - Richard Romanus, David Proval and Amy Robinson. At one point Marty was thinking of Jon Voight for the De Niro role. Voight is a fine actor, but obviously we made the right choice in De Niro!

Was using pop songs for the soundtrack instead of a traditional score Marty's idea?

Yeah, completely. Luckily, because of my background in rock music I was able to get Allen Klein (the Rolling Stones' manager), for example, on the phone and get the rights really cheap. I think we paid $1, 500 for 'Jumpin' Jack Flash'! It would probably be $1.5m now! Between us and AMERICAN GRAFFITI (1973) nobody had ever used rock or pop songs as a soundtrack before.

This was your first film as a producer. What skills that you had developed in the music business were useful in making the movie?

Honestly, the only difference between movies and music is that in music when you have 15, 000 people in an arena you cannot say "This isn't working. Let's do it tomorrow."! You don't have that luxury. When things are messing up on a movie, you can always say "Let's quit tonight and we'll start again tomorrow." Marty had so completely thought out the entire movie that he was flexible in the sense that if we had to drop one shot from a day's shooting, he still knew where he was. This came from being an editor first and then a director. It made the film a very easy experience, and I got lucky working with him for my first film. He was so prepared and proficient that he was able to finish the film in the 30 days we had. It was a close collaboration and I was on set every day.

What were some of the ideas and advice that you contributed to the film?

My only advice came during the final cut and in the music. The great movies are all made by auteurs. I think a producer is someone who makes it possible for a great director to make his film. I don't think film is a producer's medium. It's a director's medium.

What was the mood on set?

It was good. The only weirdness we had was that Bobby and Richard Romanus were not able to leave it behind at the end of the day. They stayed in character with each other. It was a little scary. Bobby tried to intimidate Richard.

Was there a feeling during the making of the film that you were making something special?

There was a feeling that it was pretty high-energy and that some amazing acting and improvisation was going on, like the scene where De Niro first comes into the bar and they go into the back room and there is a tiger there. That scene was pretty much improvised and when we saw the dailies we all said "Fuck me! This is pretty amazing!". We knew something was happening but we didn't know whether the distributors were going to dig it. In those days it was a lot different. There wasn't any Fox Searchlight or Focus Features. There were no distributors dedicated to little movies.

How much of the script would you say was improvised?

There were four or five scenes that were kind of improvised but most of it was in the original script. The back room scene was one, others included the scene in the hallway where Teresa (Amy Robinson) had the epileptic fit, and scenes where Harvey and Bobby were talking or fighting.

Did you get the feeling that Scorsese, De Niro and Keitel were headed for big things watching them at work on the film? That they had a unique chemistry with each other?

I didn't feel any of us were headed for big things! It just felt like we were doing something interesting. Marty and Harvey already had a strong relationship, but it was very interesting to see Bobby and Marty's relationship build very quickly, in terms of their trust in each other.

How worried were you that filming a lot of the New York scenes in L.A. would not work?

We only actually shot for 7 days in New York. Marty had designed the sets in L.A. in such detail (for example he insisted on tin ceilings so that you could see them) that I wasn't worried. These little details told you you were in Little Italy. Marty had already done BOXCAR BERTHA with Roger Corman so he was already good at making a little money go a long way!

Do you think the film benefits from having a small budget and a fast shooting schedule?

Limitations on artists are what make them great. I saw this in the music business, and now I see it in the film business all the time. When you have restrictions and limitations placed upon you, you have no choice but to just get on with it, and it often makes for better art. If you have all the time in the world, you never have to make a decision. Marty had to make 25 decisions a day on MEAN STREETS. Nowadays half the work is done in post-production with CGI. Actors are acting against a bluescreen!

What are your strongest memories of the shoot?

I guess just the excitement that Marty was this interesting new visionary with an intense energy that is always attractive to be around. The most compelling part of the whole period was just watching him work.

What was your reaction to seeing the film for the first time?

It was great. The cool thing was that unlike most movies, when we first saw it all cut together most of the music was already on the soundtrack. From the rough cut, Marty picked out the ideal music he wanted for every sequence and then my job was to go and get the rights! That wasn't easy!

Did you now think that it was going to make everybody's careers?

We screened it for a lot

of friends, including Francis Coppola, George Lucas and Brian De Palma, and

everyone loved it. But the first people we showed at studios hated it, Universal

for example. Thank God John Calley was there at the second screening and just

loved it. Then we were fine. John was an amazing guy. He was the most incredible

executive I have ever met. He really understood the role of the filmmaker and

the role of the studio, which was to support the great filmmaker. That's not the

way it is done now.

We screened it for a lot

of friends, including Francis Coppola, George Lucas and Brian De Palma, and

everyone loved it. But the first people we showed at studios hated it, Universal

for example. Thank God John Calley was there at the second screening and just

loved it. Then we were fine. John was an amazing guy. He was the most incredible

executive I have ever met. He really understood the role of the filmmaker and

the role of the studio, which was to support the great filmmaker. That's not the

way it is done now. After finishing the film were you now more interested in film rather than music?

Well, as soon as the film finished, suddenly Bob Dylan and The Band wanted to do another tour, so I was drawn back into the music business. And then we did THE LAST WALTZ (1978), which brought Marty back into it. It was kind of a weird circle. After MEAN STREETS, I went back and forth between music and movies. I thought they were both really valid disciplines.

What was the immediate impact for you when it came out?

About a month after we opened, THE EXORCIST came out. As far as Warners was concerned, one was a nice, small art movie that won lots of awards and the other was a movie that was going to make $100m. They were more excited by THE EXORCIST than in our film!

How does it impact on your life now?

It's one of the films that I made that I think will stand up forever, alongside THE LAST WALTZ, UNDER FIRE (1983) and TO DIE FOR (1995). MEAN STREETS is the one that has lasted the longest.

Jonathan was interviewed by telephone on 6th July 2012. I would like to thank him for his generosity and candour.

Paul Rowlands is a Japan-based writer. After completing a BA Humanities course (majoring in English and Science) at the University of Chester, he moved to Japan in 1999. He writes for the James Bond magazine, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, has had articles published on Press Play and has had an almost lifelong obsession with cinema, something the advent of DVD only increased. Paul is also a writer of so far unpublished short stories and novels, and is planning his first short film.

No comments:

Post a Comment