Richard

Rush is the celebrated director of THE STUNT MAN (1980, Academy Award

nominations for Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Actor:

Peter O'Toole) and FREEBIE AND

THE BEAN (1974). A true cinematic rebel, Rush broke his teeth directing

exploitation pictures for American International Pictures in the 60s,

and began exploring characters who are multi-faceted and capable of

being different things at different times, and live on the outside of

conventional society. His debut TOO SOON TO LOVE (1960) was described as

the first American New Wave film, and featured one of Jack Nicholson's

earliest appearances. In films like HELL'S ANGELS ON WHEELS (1967) and

PSYCH-OUT (1968), Rush helped to develop the persona that made Nicholson

one of Hollywood's most iconic and acclaimed actors. Rush also directed

the counterculture comedy drama GETTING STRAIGHT (1970) with Elliott

Gould, and the erotic thriller COLOR OF NIGHT (1994) with Bruce Willis

and Jane March. In the third part of a four-part interview, I spoke to

Rush

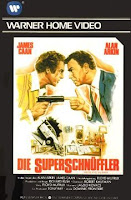

about how FREEBIE AND THE BEAN came his way, working with Alan Arkin, James Caan and Valerie Harper on the film, and the film's legacy; and about his most acclaimed film THE STUNT MAN - the themes of the film, working with composer Dominic Frontiere, and casting and working with Steve Railsback and Barbara Hershey.

Richard

Rush is the celebrated director of THE STUNT MAN (1980, Academy Award

nominations for Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Actor:

Peter O'Toole) and FREEBIE AND

THE BEAN (1974). A true cinematic rebel, Rush broke his teeth directing

exploitation pictures for American International Pictures in the 60s,

and began exploring characters who are multi-faceted and capable of

being different things at different times, and live on the outside of

conventional society. His debut TOO SOON TO LOVE (1960) was described as

the first American New Wave film, and featured one of Jack Nicholson's

earliest appearances. In films like HELL'S ANGELS ON WHEELS (1967) and

PSYCH-OUT (1968), Rush helped to develop the persona that made Nicholson

one of Hollywood's most iconic and acclaimed actors. Rush also directed

the counterculture comedy drama GETTING STRAIGHT (1970) with Elliott

Gould, and the erotic thriller COLOR OF NIGHT (1994) with Bruce Willis

and Jane March. In the third part of a four-part interview, I spoke to

Rush

about how FREEBIE AND THE BEAN came his way, working with Alan Arkin, James Caan and Valerie Harper on the film, and the film's legacy; and about his most acclaimed film THE STUNT MAN - the themes of the film, working with composer Dominic Frontiere, and casting and working with Steve Railsback and Barbara Hershey.Parts one and two of the interview.

What excited you the most about the opportunity to make FREEBIE AND THE BEAN?

Well, actually, at the

time it was offered to me it didn't intrigue me. I turned it down

several times. It was a treatment written by Floyd Mutrux that the

studio had about two corrupt cops who ride around in a police car,

quarreling with each other like an old married couple. You were never

sure which one was the wife and which one was the husband. They

became interchangeable. There was also the somewhat clumsy, rough

skeleton of the plot concerning a criminal that they must keep alive

to testify while assassins are contracted to kill him, which survived

through our final film screenplay. I liked these ideas idea but there

was nothing else there to make a movie work. John Calley, who was the

head of the studio and was the only great executive that I have ever

met in my life, asked me ''Why don't you want to do the movie?'' I

said ''I want to make a Dick Rush picture. '' He said ''Why don't you

turn this into a Dick Rush picture?'' He was very generous and

promised the studio would be very agreeable. It was the kind of offer

that you can't refuse.

So I called my writing

partner and we wrote a new screenplay about two bickering cops that

became a prototype of the buddy cop movie. I put a lot of meat on

the bones, with the unstereotypical wife of Freebie tormenting him

with jealousy and the comic relief of their relationship. I also

enjoyed holding a Funhouse Mirror up to the audience to let them

examine their own attitudes towards violence. I shot the film partly

in a Tom and Jerry style, with lots of car chases and car crashes,

and the heroes are being indestructible. The audience is laughing and

enjoying themselves and suddenly Freebie would drive around the

corner into a marching band of kids, and just sloughed through them.

The audience thought ''Wait a minute. What am I laughing at?'', and

the style of the film had changed to stark realism. There was a lot

of game-playing in the picture. At the time, we were in the middle of

the Vietnam War, and we were watching villages being napalmed at

dinner time on the TV set. Violence was engulfing our culture and it

impacted upon our morality. At the same time, we were human beings

with families and pets. It seemed to me that it was the time to play

some games with the audience in a way that would help the picture and

not hurt it.

|

| Filming Freebie and the Bean. |

Did Floyd Mutrux have

any other involvement in the film?

No. He did not

participate in any further writing or production or post-production

work, just the original piece of material that the studio handed me.

I was later hired by the financier of THE STUNT MAN, Mel Simon, to

supervise the filming of a film Mutrux was directing entitled

Pinball, but I got busy directing THE STUNT MAN, so I hired a young

director named John Theile to supervise the film instead.

There was friction

between Alan Arkin, James Caan and yourself during the shooting of

the film. Do you think it helped the film in any way?

No, but thank God it

didn't hurt the film too much. I had never had trouble with actors in

my life before that film and I have never had problems since. The

main factor was Arkin. Caan was a copycat. He was Arkin's buddy and

would do anything Arkin did. When I told John Calley I wanted Arkin

for the role he warned me''Arkin is a director killer. We just did

CATCH-22 with him and he put Mike Nichols in the hospital. '' I said

''Hell, I've never had any troubles with actors. I'll take my

chances. '' It was kind of a stupid mistake on my part. Arkin needed

conflict as part of his method, and it was horribly disruptive, but

it didn't show in his work. I found myself having to erase my own

laughter from the soundtrack because the work Arkin and Caan were

doing was so funny.

How much of the film

was re-written on the day or improvised? Did you devise any new

action sequences during filming?

The film was thoroughly

written on paper, including all the action and the dialogue, but of

course Arkin and Caan kept up a habitual banter talking over each

other, arguing and contradicting each other, which I strongly urged.

The adjusted dialogue somehow emerged through this banter and

therefore sounded completely hilarious and spontaneous. Of course

there was spontaneous action. I had never seen the location or

equipment when I wrote the stunts. It's all generated from what you

have on hand. Getting a studio to approve a car off a freeway into a

building involves a monumental campaign.

That's my favorite

scene. It's a wonderful scene, beautifully written. Valerie Harper is

a dream, and of course she was made for that scene.

Do you think there's

an element of repressed homosexuality at all in the relationship

between Freebie and Bean?

Of course. And since

Arkin and Caan are such rugged, masculine characters in reality and

in their own minds, it makes their dependence on each other more

poignant and funnier.

FREEBIE AND THE BEAN

inspired so many other buddy cop movies, but few if any had parts for

women like your film did.

No, they didn't. Most

of the copycats never 'got' what made the movie work, except for a

few, like Dick Donner with LETHAL WEAPON (1987) or BEVERLY HILLS COP

(1984).

The film shows how life

can resemble a cartoon at times, but it's still very real and actions

have consequences. I consider my major value as a filmmaker to be my

ability to walk the tightrope between comedy and drama and deliver

without falling off.

I have heard people

describe THE STUNT MAN as either a very serious drama or a comedy,

and I always insist it's both.

You're right!

Particularly on THE

STUNT MAN, it strikes me that a theme in your work is that the angle

that people see things, the information that they are privy to or not

privy to, determines the way they see the whole world.

Yes, that's very much a

quest I've been on since I've been making movies. We all have a right

to put the 'camera' in front of anything, and the angle with which we

place it will determine how something seems to you.

|

| Peter O'Toole and Rush on set. |

Exactly, and that's why

I shoot whenever I can in a subjective reality. THE STUNT MAN was

shot completely that way. You see the whole picture through the eyes

of one character. You know only what that character knows, and you're

thinking the same way as the character, as opposed to Hitchcock where

he'll take you back to the ranch to show you the bad guys plotting.

I find it amusing that

Eli (Peter O'Toole) probably isn't trying to kill Cameron (Steve

Railsback), but that doesn't mean he wouldn't allow him to die in

order to get his shot!

Yes, although Eli

doesn't know that himself!

You were connected to

THE STUNT MAN, famously, for a decade. Did your vision for the film

evolve a lot over that period?

Only slightly, because

time was eroding the screenplay and the Vietnam War was receding into

history. Our young fugitive (Francis Cameron), who was recently from

the Vietnam War, was growing older. In the final rewrite of the

screenplay I added the scene at the dinner table where Eli says to the

writer ''War is not the disease. It's only one of the

symptoms. Name the disease. What is the disease?'' And so the main thematics of the film become an active part of the plot - Name the disease.

|

| Rush and Railsback on set. |

Actually, no-one had

seen HELTER SKELTER. Steve had just shot it and it was still in the

cutting room, so I didn't know about the ferocity and brilliance he

had exhibited in the role of Manson. When I called him to read for

THE STUNT MAN, it was clear he was that innocent, West Texas kid with

the naivete that the part needed, as well as the dark, lethal

underside that terrifies Barbara Hershey about going into the woods

with him at night.

People don't often

talk about how great Barbara Hershey is in the film. What do you feel

she brought to the movie?

I think she is

seriously under-rated in the role, although she did get some great

reviews. She was asked to play a dumb young actress who, if you

opened her refrigerator, you'd probably find a wilted orchid and half

a bottle of flat champagne. She played a shallow young actress and

she captured her perfectly, while physically projecting the qualities

of the universal dream girl.

|

| Frontiere. |

Yes, they're all rebels

who relish their own strangeness of character.

The tone of your films

is quite hard to put a finger on, but your frequent composer Dominic

Frontiere is always completely in sync. What has your working

relationship been like?

The relationship that I

have developed with him is a fortunate one for me. First, the man is

a tunesmith, and haunting melodies come drippingly off his fingers as

he sits at the piano and we discuss a scene in the movie. That is how

we work. Also, he is an articulate man. Not being a professioanal

musician, I can express an idea in words which he can turn into

music. We have done three films together and I am perpetually

thrilled.

Part four.

Rush's THE STUNT MAN site.

Interview by Paul Rowlands. Copyright © Paul Rowlands, 2017. All rights reserved.

Part four.

Rush's THE STUNT MAN site.

Interview by Paul Rowlands. Copyright © Paul Rowlands, 2017. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment